A Blog Entry for Black Women in Music 4120H

The Black Bisexuals Behind the Blues

The Intersectional Rise of Black and Queer Culture

It took almost a century before blues music evolved into the blues genre we know today: raspy-voiced white men who strum their guitars while sulking into their stools. Predecessors of the genre? Black, queer performers unafraid of fluidity in gender and sexuality.

As the blues branched off from its sister genre, jazz, in the early 20th century, blues music was as marginalized as its performers. The stigmas surrounding the genre were a result of the taboo lyricism. Early blues queens sang raunchily about sex and gender, with lyrics that explicitly alluded to queerness.

The rise of blues queens Ma Rainey and Bessie Smith solidified the legacy of blues music in American history. Like so many Black musicians, their impact was not confined to their music alone. The two women pioneered an era of Black expression in which their art was finally given a platform. The vulnerability of navigating romantic sapphic relationships in their lyrics became some of America’s earliest documented queer art.

Ma Rainey

Ma Rainey, born Gerturde Pridgett in 1886, was the first blues queen to reach celebrity status. Renowned as the first great blues vocalist, she was crowned the title “Mother of the Blues” early in her career.

As the spotlight shone onto her, so did the rumors about her sexuality. Rainey, however, was unbothered. In fact, her story shows us time and time again how these whispers did nothing but embolden her pride. Ma Rainey was expected to crumble after her arrest for hosting a lesbian orgy in her Chicago hotel room. Many assumed this would be the end of her career; however, Rainey decided to combat the rumors about her sexuality through song.

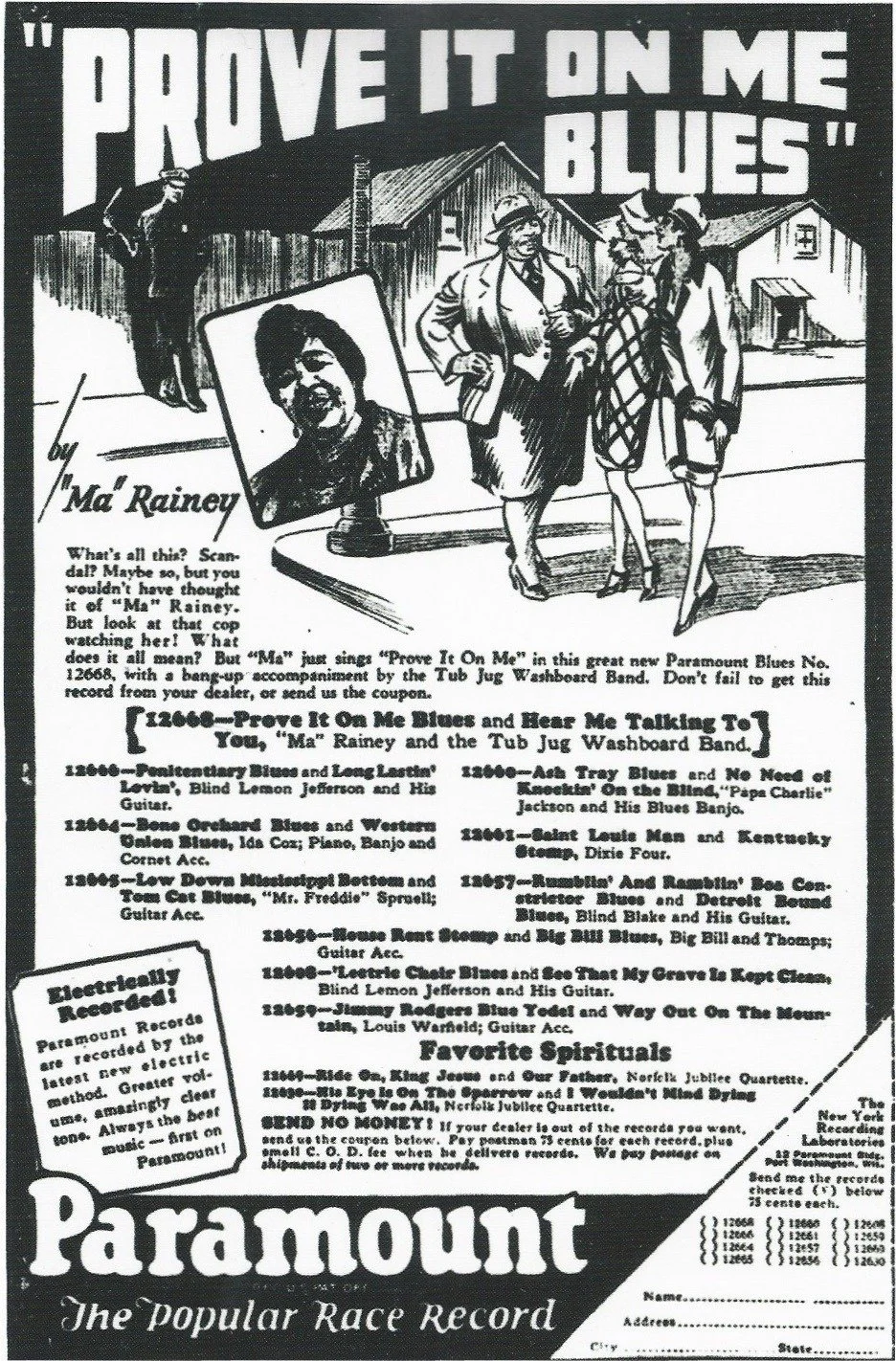

Despite never publicly commenting on the incident, nor her queerness, she wrote “Prove it on me Blues,” just a few years later, which she went on to perform in full drag. The lyrics sang colloquially about dressing like a man and flirting with women. The tune became famous for the way it taunted a heteronormative audience to ‘prove it on her.’

Bessie Smith

As the “Mother of the Blues”, Rainey became a mentor to her protégé, Bessie Smith. Despite the blatant homophobia of the time, openly bisexual Ms. Smith quickly blossomed into the biggest blues star of the time., According to vocalist Linda Tillery, “Bessie Smith started having relationships with women. It was very much a taboo in the society at large and more of a taboo in the African American community. But she found a way to be all of the people she was and live out all those aspects of her personality.” Bessie Smith made little secret of the affairs she had with her partners of both genders. She even embraced her reputation for “making her way through” chorus lines. Despite her marriage to Jack Gee, Smith had a not-so-secret affair with a dancer named Liliana Simpson. In an intense argument with Lillian after a performance, she was quoted yelling “I got twelve women in this show, and I can have one every night if I want it!”

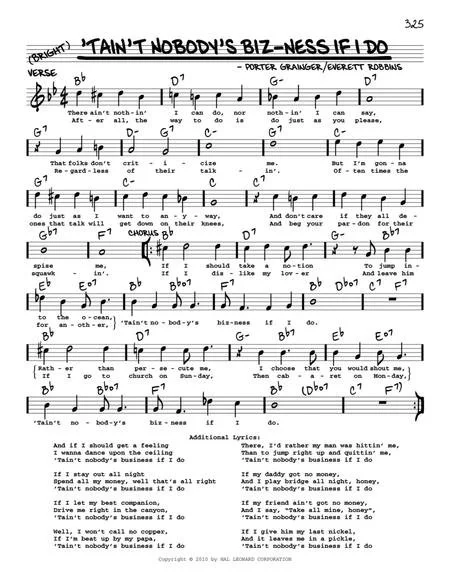

Smith and Rainey remained unperturbed by society’s homophobia. In fact, their willingness to spend life with whichever romantic partners they preferred made them seem that much more glorious to their misunderstood fans in America at the time. Similarly to Rainey, Bessie Smith also weaved her sexuality into her lyrics. Specifically, in the proud yet ambiguous song, “Ain’t Nobody’s Business If I Do,” Smith sings about women loving women. The song is not explicitly queer. Rather, it is queer in the ways she alludes to society’s intolerance of her desires.

The Blues owes a lot to queer women, in fact; without the few queer women who pioneered the genre, its impact would have been woefully minimized. An absence of Rainey and Smith’s stardom would not only have altered American music history forever,but America’s queer history as well. Rainey’s “Ain't No Business What I do” became an anthem for queer-identifying Black Americans. Smith’s unguarded attitude about loving women inspired listeners across the nation. For the first time in American history, openly queer individuals were being proudly represented in the media. Despite mainstream homophobia challenging the fame of gay performers, history watched as they were embraced within their community and rose to stardom.

As many queer, black Americans rose in the social rankings in Harlem, it became impossible to even get a glimpse of socialite status without being tolerant of bisexuality. Due to the vocality of queer leaders in the Harlem Renaissance, this era of “black awakening” ran parallel with a “queer awakening.” The Harlem Renaissance was spearheaded by those who wanted to reinvent what it meant to be Black in America. However, this is not to say that homosexuality was embraced by the entire movement. Muhammed Shareef writes in his article “Black and Queer in the Harlem Renaissance” that “Queer Black people were the antithesis to White racism and to Black heteronormativity. Queer artists of the Harlem Renaissance thus utilized the campaign to explore variances in gender expression and to take pride in both their race and their same-sex desires.” As this progressive agenda developed in Harlem, so did its corresponding anti-movement. Most notably, some Black preachers in New York at the time took charge in reinforcing heteronormativity as a core value of the black community.

Rainey and Smith were not alone in embracing their blackness and queerness through art. Richard Nugent, Wallace Thurman, Gladys Bentley, and Claude McKay were among many other prominent queer voices at the time. In fact, the earliest documented performance of blues music was executed by a man in drag. Whether or not these performers openly identified themselves as such, their music was intentionally queer coded. Whether it was through poems, essays, lyrics, art, or music, Black artists who felt comfortable exploring sexuality and gender finally found an accepting audience.

These facts pose the question: why did so many rising black stars at the time happen to be queer? Perhaps the genius behind the Harlem Renaissance did not happen to be queer, but their queerness put them in a position to feel more free and express this liberation in a more candid way. The blues exposed the heartache and turmoil caused by America’s shameful history with the Black population. The blues offered a critique not only on race relations, but the relationship between self and gender.

Those who rose to fame were characters who felt comfortable experimenting with their identities. In his essay “The Black Man’s Burden'' by Henry Lewis Gates, Gates writes that “The Harlem Renaissance was surely as gay as it was black.” The established correlation between black and queer expression throughout the Harlem Renaissance informs us that the gay-rights movement was well underway decades earlier than Stonewall. Moreover, we can solidify that the work of queer-identifying blues queens first lit the spark of the gay liberation we experience today.